By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 14, No. 5 on March 10, 2005.

One of the recurring themes in option-oriented media articles is that the $VIX Index is “too low.” Since many observers – media and traders alike – view $VIX as solely a contrarian indicator, this is a danger sign for the market. These observers figure that such a low $VIX implies that traders are, in general, too complacent, and thus the market is ripe for a beating. There are a lot of errors in these observations and opinions, and so we’d like to set the record straight. We have written articles about similar topics in the past, but with $VIX hovering near nineyear lows for such a long time (at least three months now), it is perhaps more timely now than ever.

First of all, one needs to understand that $VIX is not primarily a contrarian indicator only. In reality, it is just an index – a measure of the implied volatility of $SPX options. Most of the time, index option traders are not acting in a way that would indicate their behavior should be viewed in a contrarian manner. In general, a contrary indicator is only useful when the masses are acting in a uniform manner at major turning points. That is, if “everyone” is bullish at new highs, that is probably the top of the market. As far as $VIX is concerned, it means that if the vast majority of option traders are acting in concert, then perhaps it would be one of those times that $VIX could be viewed as a contrary indicator.

So, the question is, “Are option traders acting in concert at the current time?” It doesn’t really appear that they are. More about that later.

Another clue to whether or not $VIX can be interpreted as a contrary indicator is whether or not it is trading at significantly different levels than actual statistics would suggest. In other words, we know what the actual volatility of $SPX is. Is $VIX significantly different from that or not? If it is, then there might be a contrary trading opportunity as option traders are forcing their opinion into the option pricing structure. And when there is a unanimity of opinion, that’s when a contrary trade arises. This is most easily seen at market bottoms, such as July 2002, October 2002, or March 2003. In each of those cases (and many others throughout history), $VIX was trading at levels far above actual volatility, because (a majority of) traders expected the market to collapse. Instead, each was a market bottom – so the inflated $VIX was a classic contrarian buy signal.

What about today’s levels? The following table shows the relevant actual (HV10 means 10-day historical volatility) and implied volatilities of the major indices. This data is taken from one of the many reports available daily on The Strategy Zone and the same data is also updated once a week on the free area of our web site, at http://www.optionstrategist.com/free/analysis/data/index.html.

Data as of 3/8/05 close:

| Index | HV10 | HV20 | HV50 | HV100 | IV |

| $SPX | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11.2 |

| $OEX | 8 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10.8 |

| $DJX | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10.4 |

| /SPH5 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10.00 |

$VIX: 12.40

The implied volatility (IV) shown in the rightmost column above is the composite implied volatility for each index, computed by using the individual implied volatilities of all the options and weighting them in a manner that gives the most weight to the heaviest-traded, at-the-money options (the exact formula, if you care, is in the book Options As A Strategic Investment). $VIX is computed in a slightly different manner, and so it has a slightly different value.

Looking at the above figures, do you think $VIX is too low? It certainly doesn’t look that way to me. $VIX is higher than every other historic or implied volatility shown in the table. This is a big hole in the argument that traders are “too complacent.” If traders were, we’d expect to see $VIX at least as low as some of the values in the above table, since $VIX generally trades with some premium to actual volatility – it’s just the nature of the way that $SPX index options have always been priced (over-priced).

In other words, $VIX is low because actual volatility is low, and for no other apparent reason. That’s not “complacent,” that’s just the way it should be.

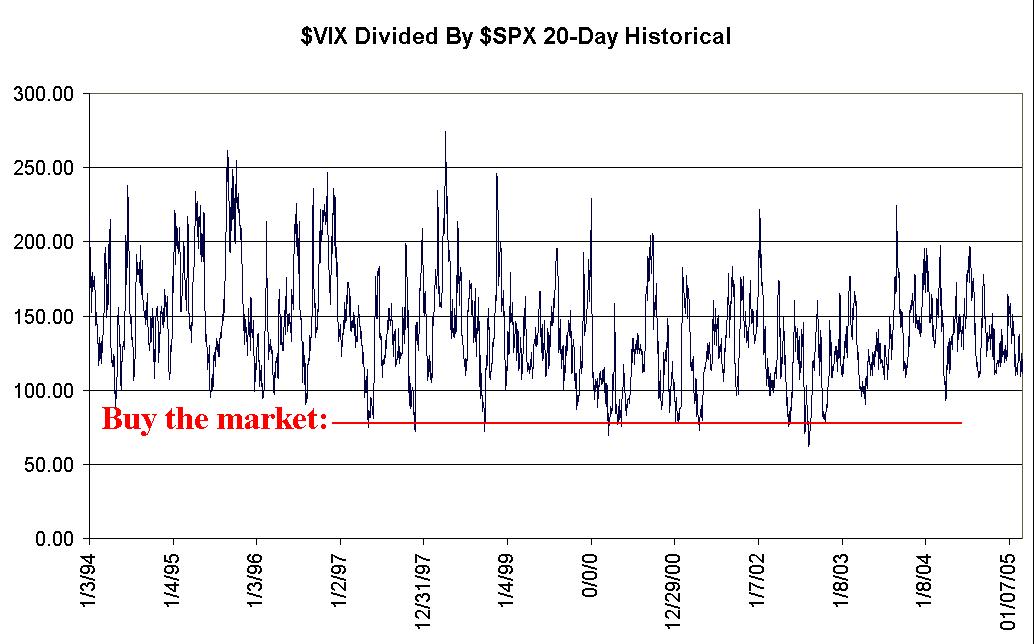

Figure 1 shows a comparison of $VIX with 20-day historical volatility on all dates going back to 1994. A reading of 100 on this chart means $VIX is equal to the 20- day historical. As you can see, most of the time, the line on the chart is above 100 – i.e., $VIX is above historical (we mentioned that before). In fact, if $VIX dips below historical, it is usually a buy signal. That may seem counter-intuitive at first, but what typically happens at market bottoms is that the market is collapsing so fast that historical volatility actually shoots above $VIX. The red line on the chart marks those extremes. However, those all occurred when $VIX was high – not when it was low, as it is now.

At the far right hand side of Figure 1, you can see that currently the graph is at about 120 – $VIX is about 20% higher than 20-day historical volatility. This certainly is not out of line with past readings. Hence, this further strengthens our contention that $VIX is where it’s supposed to be because historical volatility is so low.

Just as a final point: high readings on Figure 1 don’t seem to have much of a correlation to the broad market. Sometimes those high readings preceded sell signals, but at other times they didn’t. So, the value of Figure 1 is 1) to determine if $VIX is out of line, and 2) to signify buy points for the broad market if $VIX drops significantly below historical.

What Does A Low $VIX Mean?

You might rightfully ask, “Doesn’t the low $VIX mean anything?” Of course it does. As our friend John Bollinger is fond of saying, “Low volatility begets high volatility.” In other words, volatility generally trades in a range, and when it’s near the bottom of the range, the only logical place it can go is up.

This is one reason why we think an excellent trade is to own a long position in the VIX or Variance Futures (Position F262, page 4). We have been saying for some time that we want to “own volatility,” and this is the easiest way to do it.

But does this low $VIX have ramifications for the broad market? This is a subject on which we have written much in the past. Suffice it to say that a low $VIX generally means the market will make a volatile move – usually in the direction of the major trend of the market. Hence, in the ‘90's, low $VIX readings generally preceded strongly rising markets. Since 2000, however, low $VIX readings have preceded market declines. If you are unsure of the major trend of the market, you can buy straddles, waiting for the breakout in either direction. Ever since the bottom in late 2002/early 2003, the market has generally declined after low $VIX readings, perhaps indicating that we are still in an overall bear market.

We often get questions such as “How can volatility increase when the market is rising? I thought a rising market meant lower volatility.” True, most of the time, a rising market is accompanied by lower volatility. But not always. Consider this sequence of closing prices, where a stock advances by exactly one point each day: 50,51,52, ...,68,69,70. The volatility of that 20-day sequence is 2.7%. Now consider this sequence: 50,52,51,53,52,54,53,... where the stock is only advancing a net of one point every two days – but does so by rising two points on the first day and falling a point on the second day. What do you think the volatility of the second sequence is? It’s 44.3%!!! That’s how a market can become more volatile even when rising.

Currently, the market has been behaving more like the first sequence. If it starts to behave like the second, volatility will rise and so will the market. Regardless, even if the market does decline from here, it’s not because traders are complacent. It’s because a higher volatility period is “due.”

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 14, No. 5 on March 10, 2005.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation